When the Mee family, made up of husband and wife Peter and Zoe, their two children, Charlie and Emily, and Charlie’s wife Charlotte, talk about sustainability, they do not just mean working in harmony with the environment to reduce carbon footprint and improve soil health.

They place equal importance on the financial sustainability of the business.

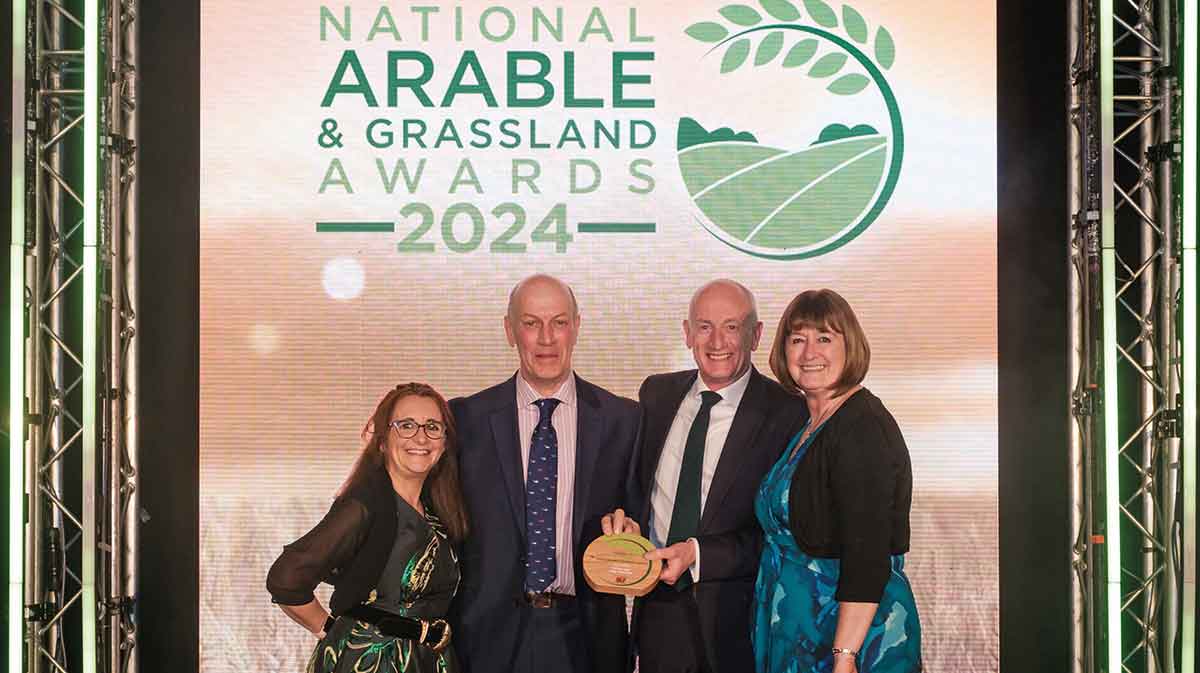

Zoe and Peter Mee won the Sustainability Award at the 2024 National Arable and Grassland Awards © MAG/Colin Miller

See also: Profile: Journey to grow top fruits

A brief rundown through the company history proves as much. Peter and Zoe were initially working on Peter’s family’s farm, located near the Dartford Crossing.

The pace of development in the area made it clear that any meaningful expansion would be impossible, and the farm could not support the growing family.

Looking for another place to farm, they seemed Scotland bound, until they came across their current base at Nassington, just outside Peterborough.

It didn’t take long for them to seek further opportunities. Alongside the 283ha owned by the business, Peter and Zoe tendered for contract-farming agreements, doubling the area farmed.

“The focus was always on being able to justify the cost of the equipment,” says Emily. “We made the most of our grain storage, taking on contracts with Frontier to hold 8,000t of wheat and around 500t of oilseed rape.”

Undoubtedly, the most substantial diversification on the farm was the decision to move into soft fruits. The idea was initially floated by the farm’s previous agronomist.

“He had moved to Poland for work and spoke to my dad about the opportunities he had seen in the blueberry market,” Emily adds.

‘We don’t even like blueberries’

The family were dubious at first. “We told him that we didn’t like blueberries,” explains Emily.

“However, in 2010 we agreed to travel to Poland to see some of the farms out there. Turns out we really liked blueberries, especially straight off the plant, and we started to seriously consider the opportunities.”

It took more than three years of planning to make Mee Blueberries a reality. One of the biggest barriers to growing blueberries was the upfront investment, with no saleable yield from the plants for three seasons.

Peter and Zoe joined the fruit cooperative Berry Gardens Growers, and then had the cost of the polytunnels and the plants.

“We had one advantage,” Emily says. “We already had an irrigation licence for the River Nene because we used to have potatoes in the arable rotation. It made sense for us to make full use of this, so we kept hold of the licence for the blueberries.”

Planting started in 2014 and the Mee family were careful not to overextend themselves.

]A total of 18ha is currently set aside for blueberries, but this was planted over the course of five years. This has not only spread the investment, but it also enabled them to conduct small trials to justify every expenditure.

“The polytunnels are a huge cost, so we explored growing them outside, but this only proved the importance of the polytunnels, justifying that cost to us,” says Emily.

“We also looked at the viability of pruning the plants. This is a labour-intensive process throughout February and March, with four or five people working full time.

“However, when we singled out an area to not be pruned, the plants grew outwards and the berries they produced were too small to meet our specifications.

Pruning focuses the energy of the plant into berry production, so once again the cost of this was justified.”

Doubling down

When the first small yield of blueberries came through in 2017, they were sent to an offsite packhouse.

The additional handling and transport of the berries led to an increased amount of waste, affecting not only the sustainability of the process, but also the bottom line of the company.

“It became clear very quickly that we needed to bring more of the process in-house. Once the plants reach maturity after six years, you can be producing up to 3kg of fruit per plant, so the amount of waste was only going to go up,” explains Emily.

Plans were put in place for an on-site packhouse, now overseen by Charlotte.

While this marked a significant investment – and risk – for the family, this vertical integration has not only reduced waste, but also opened additional avenues for them.

Last year, 184t of blueberries were picked and moved into the packhouse, with 50 workers on the picking team this year, and another 10 in the packhouse.

Of this, 162t were packed for retail customers – including Marks & Spencers, Lidl and Waitrose – and 10t was deemed unusable and sent to a local farm to be used as pig feed.

The remaining 12t met all the specifications but was already ripe and would start to lose some of that freshness after five days on a supermarket shelf.

Having tonnes of high-quality produce on the farm enabled the company to look at direct-to-consumer sales.

Overseen by Emily, Mee Blueberries offers a range of jams and chutneys, juices, liqueurs and a sparkling wine through its online shop, as well as holding a pop-up shop twice a month during harvest to sell punnets of fresh blueberries to people in the local area.

Sustainably arable

While the blueberry enterprise might have been the headline news for the company in recent years, the bulk of the year remains focused on the arable rotation, which is overseen by Charlie.

The 282ha owned by the farm is focused on wheat, with two winter wheats followed by spring oats and winter beans.

Charlie has been the driving force behind the move to regenerative farming, with the support of Peter and Zoe, working with one full-time operator.

As with every part of the business, the family have worked with others to limit investment, or otherwise find additional work for the equipment onsite, allowing to farm to operate with a reduced fleet.

Local dealer Ben Burgess supplies the tractor power, with John Deere machines used throughout.

The family has also invested in a John Deere T670i combine harvester with a Draper header and arranged a deal with a local farmer to do their combining in exchange for them doing the direct drilling, either with a Horizon DSX or a Weaving Sabre.

“As soon as the harvesting is done, we try to run through the field with our stubble rake and the Horsch Joker, which is fitted with a seeder box, to establish a catch crop,” Charlie says.

“Our aim is to always have something growing in the ground and once we’re ready to sow the next crop, we run through with a roller and drill directly into the cover.”

The use of catch crops has made a marked difference to the soil structure of the farm.

“We used to have a lot of trouble with flooding, but this has lessened with every passing year. Having the green cover provides a mat that we can travel on, so even last year, when the weather was horrendous, we were able to get most of our crops in without too much trouble,” he says.

Fertiliser reduction

Efforts to cut the carbon footprint of the business have also seen a reduction in artificial fertiliser use, with the contract farms receiving 180kg/ha and the owned ground just 150kg, in contrast to the 220kg previously applied.

“The cover crops have boosted nutrient levels across the board, and we’ve been able to drop insecticide applications as well.”

In addition to this, Charlie and Peter have established multiple compost heaps using bought-in chicken muck, spent hops, horse manure and bark, which is applied at a low rate to build hummus in the soil.

During quieter periods, the arable side crosses over with the horticultural side, providing general maintenance throughout the packhouse and helping erect the polytunnels.

Oilseed rape was dropped from the arable rotation due to flea beetle pressure, but this had the benefit of pushing harvest back and allowing them to help with the blueberries at the start of harvest.

Now Charlie is looking at more ways to reduce inorganic inputs and is exploring grant options for a Horsch Avatar drill with 25cm spacings.

“With autosteer, we would be able to alternate the crop rows each year to further develop the soil structure, and we could look at the viability of mechanical weeding.”