The benefit of beetles made for an interesting workshop at Groundswell. Rothamsted Research is working to assist growers in identifying and monitoring beetle species which could enhance integrated pest management (IPM) strategies.

Creating and improving habitats for carabid beetles (also known as ground beetles) could benefit integrated weed and pest management strategies, reducing the reliance on chemicals.

See also: Hutchinsons’ Omnia updates help optimise production

Rothamsted researcher Dr Kelly Jowett explained that there are more than 350 species of carabid beetles in the UK, 30 of them highly beneficial for farming.

Of the 30 species, each has a role to play. Carabids consume crops pests and weeds, but many have a discerning palate. For instance, the sienna flat beetle is rather fond of cabbage stem flea beetles, and the common shoulderblade has a preference for slugs.

Carabid diversity

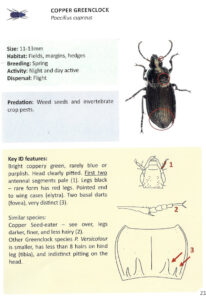

Their effect can be significant. “These are the hyenas of the beetle world. Species such as the copper seed eater or copper greenclock can consume up to 4,000 weed seeds/sq m a day,” said Dr Jowett.

In her view, monitoring and knowing the diversity of carabids on farms can only improve IPM strategies further, as it will help growers identify which predatory species are most beneficial to their farming system.

If this helps minimise pesticide use, many farmers will also see the benefits in terms of other beneficials. They often take longer to recover from insecticide use, especially carabids. “Carabids have longer reproductive cycles compared to many other insect species. Repeated use of insecticides has a detrimental effect on populations,” she added.

This was the focus of the workshop, to help agronomists and growers identify different species, allowing them to monitor the predatory potential of their systems and make any habitat changes to support a diverse species of carabids.

Carabid diversity is important, because with different species predating different pests, the cumulative effect can be the basis for a formidable integrated pest and weed control.

Carabids can be fussy

But achieving that isn’t straightforward, as carabids are not just fussy about what they predate but also the habitats and conditions they prefer.

The strawberry seed beetle favours open, dry habitats, while the hair-trap is more likely to be found near water. “The good news is that one species is bound to thrive in any given year,” added Dr Jowett.

With carabids being different, there is no one-size-fits-all approach, so Dr Jowett advised the audience to adopt testing to identify any shortfalls in species diversity.

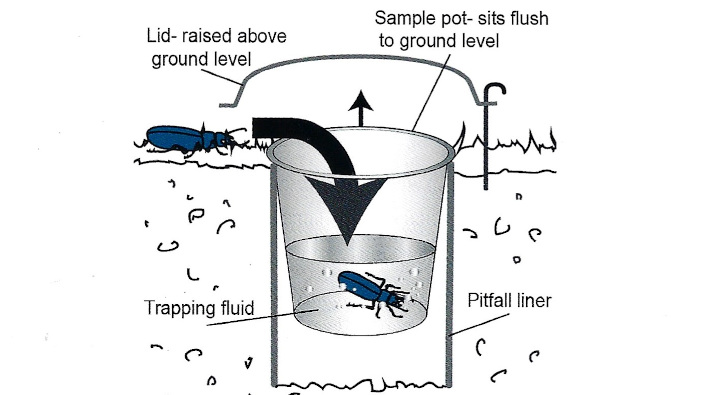

She explained that trapping isn’t complicated. A jar, cup or container at soil level filled with water with a drop of unscented detergent will suffice for them to just fall in. Dr Jowett advised a seven-day trapping period is probably best.

There’s plenty farmers can do to support populations, from beetle banks to creating field centre habitats like flower strips, greater crop variety and specialist habitats like ponds.

But Dr Jowett stressed that whatever was undertaken, year-round food and shelter, and a place to breed, are vital.

Farmland carabid guide at hand

Trapping might be simple, but identification can be more challenging, often requiring a microscope, so Rothamsted Research has created a guide. This doesn’t just offer guidance on species identification but also their particular farm benefit, dispersal, behaviour and habitat.

It groups species by size, colour and shape, which then allows users to identify specific species through more detailed information. There is also advice on trapping.

It groups species by size, colour and shape, which then allows users to identify specific species through more detailed information. There is also advice on trapping.

But Rothamsted is looking to refine this further. It wants farmers to get involved in the Carabid Monitoring Programme.

“We want to understand more about their behaviour and lifecycle and then design approaches to how growers can attract greater carabid diversity and get them where needed,” added Dr Jowett.

Rothamsted wants farmers to monitor carabids in field margins, adjacent field areas and field centres. That’s because a recent study has questioned the effectiveness of field margins.

“I don’t want to underplay the importance of field margins, but we looked at various margin options to evaluate the effect on carabid diversity. Rather than confirm our hypothesis that a higher density would be found in field margins and 5m adjacent field area, greater abundance was found in field centres.

“What we need to do now is look at in-field interventions that can support carabid populations. We’ve found that undersowing oats with a grass/clover mix supports beetles and larvae, and that the surface chaff through reduced tillage benefits the snail- and slug-hunting species.

“The more data we can collect covering an array of farming practices and systems, the better.”

Use carabids to check system change success

Dr Jowett also stressed carabids were great for gauging the success of any farming system changes.

“Carabids are very sensitive to environmental change. Growers who want to measure the effects of farm management changes just need to monitor carabid populations and species diversity.

“It will quickly highlight whether the changes to the farming system have been beneficial or otherwise.”