One of the design features that contributed to the success of Henry Ford’s Model F Fordson tractor was joining the engine, gearbox and final drive to form a rigid structure replacing the traditional steel girder frame. Mike Williams reports.

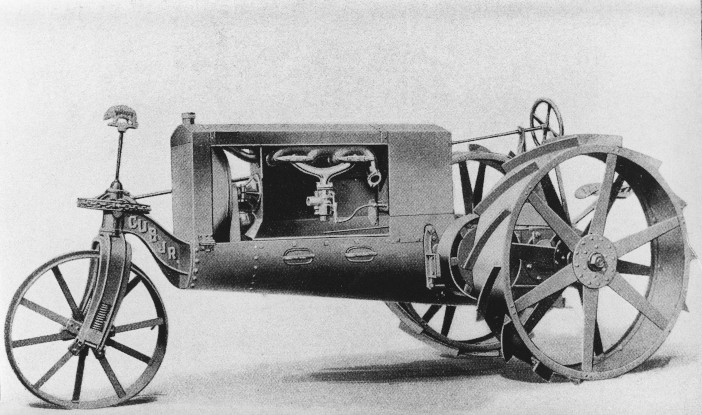

The first of the Model Fs came off the production line in 1917 and it soon became the biggest sales success the tractor industry has produced, but it was not the first tractor to avoid a steel girder chassis. The Wallis company, also based in America, had introduced their U-frame in 1913 when they announced their new three-wheeled Cub tractor, and it remained a design feature on various Wallis and Massey-Harris models until the early 1940s.

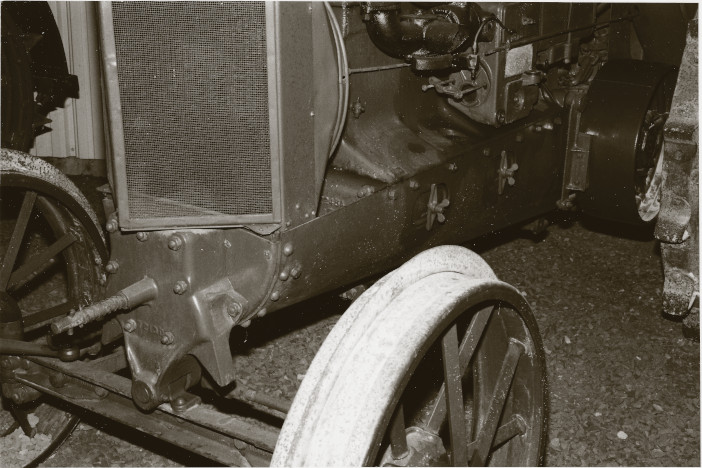

The Wallis U-frame was made of boiler grade steel plate and, as the name suggests, it was formed into a curved shape with immense structural strength, providing a base that carried the engine and other major components. The first version of the U-frame designed for the Cub tractor supported the engine and gearbox, but later versions were extended to include the final drive as well. The main benefits offered by the U-frame were similar to those available later from the Fordson’s frameless design and included a high degree of rigidity, it provided a dirt-proof seal and the U-frame also offered sturdy protection against damage caused by contact with large solid objects such as tree stumps. The Fordson structure probably had lower production costs and it was also designed to suit the high output, mass production methods used in Henry Ford’s factory.

Wallis introduced the U-frame at a time when competition was increasing as the World War 1 sales boom in America encouraged many more manufacturers to move into the tractor market, but the Cub was a popular choice and the patented U-frame design appears to have been a significant factor in its sales success. The U-frame had been developed by Wallis company engineers working on the new Cub tractor at a time when Wallis had close links with the J I Case Plow Works company. Both companies made farm equipment, they shared the same factory in Racine, Wisconsin, and there were family links between the families that owned the two companies. In 1919 the two companies merged under the Case Plow Works name while retaining the Wallis brand name for the tractors.

Bringing the two companies together appears to have given a boost to Wallis tractor development, including engine updates that boosted the power output while achieving some of the best fuel efficiency figures available. The Wallis 20-30 model was an example, introduced in 1919 with the model numbers indicating 20hp available at the drawbar with 30hp at the engine flywheel, but these figures were easily exceeded when the tractor was tested at Nebraska in 1927 with maximum power outputs of 27 and 35hp respectively. In the World Tractor Trials held in England in 1930 only one of the entries achieved better traction efficiency than the 20-30, and in the same trials Wallis tractor models – now carrying the Massey-Harris name – achieved two out of the top three results for fuel efficiency. Fuel costs were an important factor during the 1920s because of slender profit margins for farmers in the United States and in Europe, and the performance figures and the U-frame were attractive factors at a time when the Fordson’s low price was a big influence in the market.

Massey-Harris interest in the Wallis tractor performance and design features started in the mid-1920s. At that time Massey-Harris was easily the biggest farm equipment company in Canada, with an international reputation as one of the world’s leading manufacturers of harvesting machinery including mowers, reapers and binders, and they would soon emerge as a world leader in combine harvester development and production. One of their problems was the fact that the Massey-Harris success story did not at that stage include tractors, as previous attempts to move into the market by selling tractors through some form of production or marketing link with American companies were not successful, leaving Massey-Harris with no tractor to sell.

Wallis tractors would be the best choice to fill the gap in their product range, Massey-Harris decided, and negotiations with the Case Plow Works began in 1926. The situation was apparently complicated and at one stage there were unwelcome rumours that Case was trying to buy Canada’s biggest farm machinery manufacturer. Instead, a deal announced in 1927 allowed Massey-Harris to sell Wallis tractors in Canada and in some limited areas of the United States, and this was followed in 1928 by news that Massey-Harris was buying the Case Plow Works company in a deal that included the Wallis range, other Case Plow Works products, plus the right to use the Case trade name.

It was an excellent deal for Massey-Harris, bringing them a tractor range that had earned a good reputation, an established factory in the world’s most important farm equipment market, and there was also an added bonus for the new owners. At that time there were two J I Case companies in the United States, both named after Jerome Increase Case, the threshing machine pioneer, both making farm equipment including tractors, and both based in Racine. When the Case Plow Works sale was announced, the J I Case Threshing Machine Co owners were concerned that Massey-Harris might exercise their newly acquired rights to use the Case brand name, so they paid $700,000 to buy the rights – effectively reducing the net cost of buying the company by almost 30 per cent.

The Wallis acquisition transformed the position of Massey-Harris in the tractor market. The tractors were sold under the Wallis name initially, but this was soon replaced by the more familiar Massey-Harris brand name. And the new owners also made good use of the sales appeal of the distinctive U-frame feature, describing it in their 1929 tractor publicity as “unquestionably the greatest invention in tractor history” and emphasising the light weight and great strength of the U-frame in their 1940s advertising.

Read about other ‘Whatever happened to….’ articles here