If we maintain the current usage rate of phosphate applications, global sources of the valuable nutrient may only last another 30 to 100 years. Now, a new in-field soil testing kit, developed as part of the Phosfield project, could help farmers more precisely utilise the available phosphate.

Funded by the European Regional Development Fund’s Agri-Tech Cornwell programme, the kit is said to provide precise results within just 20 minutes, significantly reducing the several day turnarounds provided by laboratories.

“Most farmers test their soils for phosphate every three to five years,” explained Dr Susan Tandy, soil scientist at Rothamsted Research. “They usually take several samples from across the field and amalgamate them to get an average reading.”

The phosphate level will vary across fields, and more accurate GPS-located testing will enable farmers to apply fertiliser at variable rates, therefore achieving more consistent yields. Phosphate availability will also change over time and depends on the soil type, so more frequent testing will allow farmers to be even more accurate.

This new test has been in development for three years and has been trialled in Ghana, where it is believed it will have significant benefits.

“The technique would be extremely useful in developing countries as they have limited lab access to test their soils, meaning the application of expensive fertiliser is both financially risky and may not match crop requirement,” said Dr Tandy.

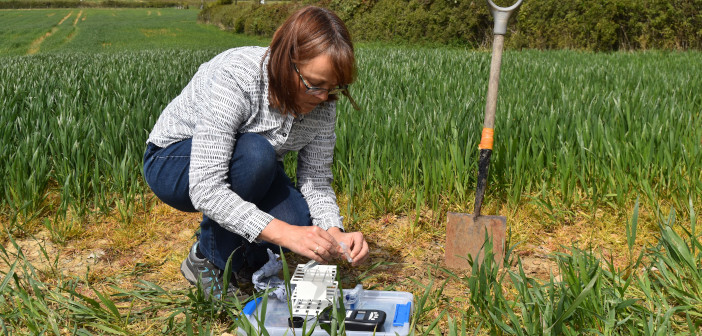

Using Cornish soil samples, the researchers have worked with Vital Spark Creative to produce an analytical kit that will be easy to use in the field.

“There are lots of different elements to the kit; if you’re not a chemist it’s pretty involved,” said Chris Booker, director at Vital Spark Creative. “We tried to make it user friendly so that farmers can easily use it on the farm.

“You put a small soil sample into the bottle and mix it with an extraction solution before passing it through a filter. You then add various chemicals to get the final result, which is analysed in a colourimeter so the result is easy to read.”

The results are said to be precise and can be translated into a phosphate index if required.

“The attraction of it, beyond speed, is that this test may well prove more accurate for different soil types,” added independent agronomist Tim Martyn. “The phosphate fertiliser recommendations in the Nutrient Management Guide (RB209) are not soil type specific. Given the limited world phosphate supplies, more accurate measurement means we can be much more efficient with these resources, particularly in developing countries. It’s really exciting.”

Dr Tandy explained that while precision farming techniques like soil and crop scanning and conductivity tests enable variable rate nitrogen applications, analysing phosphate will likely always require a physical soil sample to be taken. The test could therefore form the basis of more efficient applications.

“By not over-fertilising, farmers will be saving money and potentially reducing phosphate loss to watercourses, which causes damaging pollution via eutrophication and resultant algal blooms,” she said.

It is also said to be cost effective. After the initial cost of the kit, each test will cost pence rather than several pounds for laboratory analysis. While it’s not commercially available yet, the team are seeking additional funding to bring it to market and will undertake further research to provide tailored fertiliser recommendations for different crops and soil types.