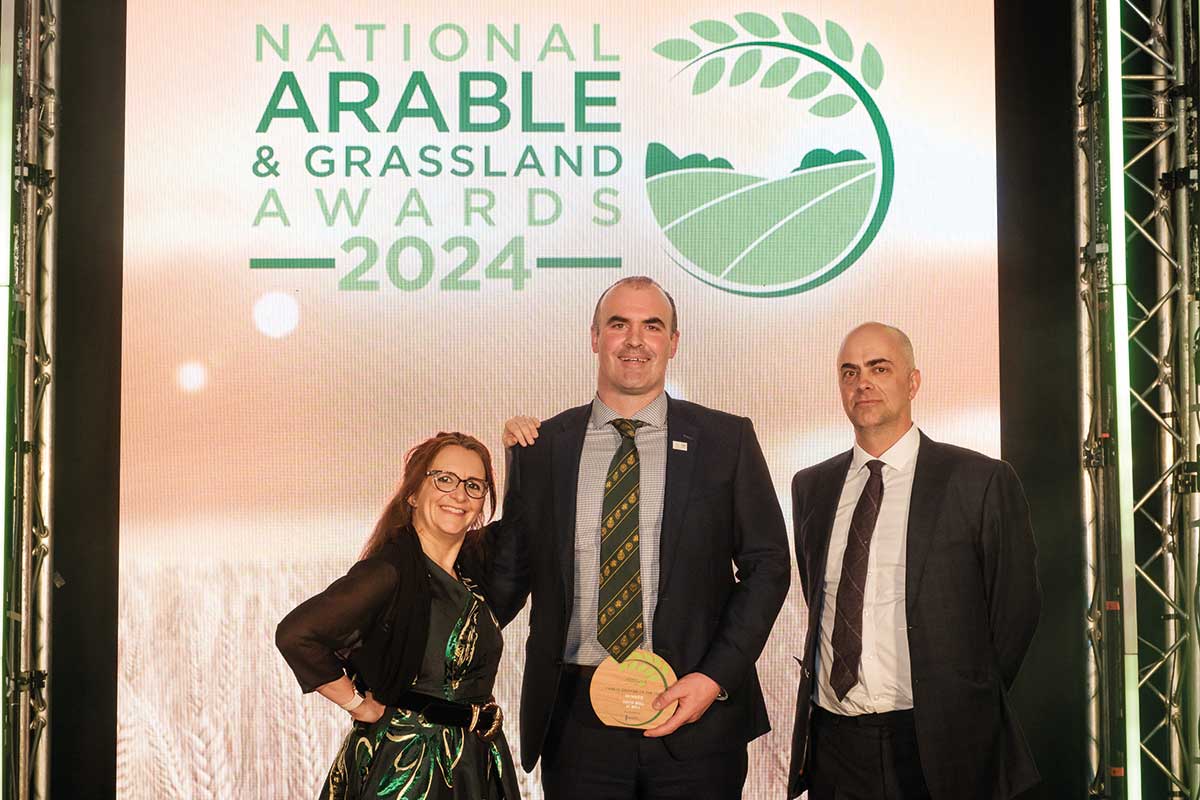

Having won the Farm Manager of the Year title at the 2022 National Arable and Grassland Awards (NAGA), David Bell found success again at the 2024 event, taking home Cereal Grower of the Year.

Based in Fife, he farms just over 800ha with a diverse rotation, a moderate fleet of equipment and a team which he says he can trust to manage operations when other commitments pull him away.

See also: Profile: Journey to grow top fruits

Sitting outside the farmhouse and enjoying some late-July sunshine, David says he believes much of his success has come from engaging with the wider industry.

He has spent time as chairman of the Voluntary Initiative to increase the use of integrated pest management systems in Scotland, and sits on the AHDB Cereals & Oilseeds Sector Council.

“I’m cautious of becoming too insular,” he says. “Going off farm and seeing how other people work has been instrumental in making me a better farmer. Peer-to-peer learning is one of the most powerful tools we have as an industry.

“Being able to see what has worked, in what conditions, and cherry-picking ideas is something everyone is able to do if they engage with the groups that are available.”

He adds that, like many, he is standing on the shoulders of previous generations as he has transitioned the business to be more sustainable and profitable.

“Seeing how growers are adapting, not only in the UK but further afield, helps me to incorporate new ideas and build on what has come before.”

Adding to the farm

David had the opportunity to put new ideas to the test last year when he invested in a 100ha neighbouring farm.

It came at the right time, as the business was brought out of a tenancy in the same year. It meant the new ground filled a gap and brought the hectarage closer to the base, increasing the efficiency of all operations.

He says the arable ground has now been ringfenced at the base, with the majority of the further-away ground set aside for grass.

“We’ve fluctuated in size over the past 10 years,” he said. “We were up to 1,200ha and, after a period of downsizing, we’re starting to build back up again. It was obviously a huge decision for us to purchase the new farm, but it will give us various opportunities for diversification and it’s a boost when the bank has enough confidence in you that they will back you up in this sort of investment.”

The new farm comes with additional shed space, which means more of the equipment can be kept under cover. There is also a farmhouse, which was occupied by a stockman but will now be rented out for additional income.

Skills sharing

“We have been integrating more livestock, alongside the Aberdeen Angus-cross herd, into the business, but I want to share these skills and the workload across the full team – this takes pressure off individuals and builds up each member of the team.”

While the benefits have been significant, the new ground has come with its own series of challenges – many of which were exacerbated by the bad weather that dominated the autumn and winter of 2023.

David explains that they managed to get through the potato harvest, and even established winter cereals, but as the wet weather continued into spring, issues started to become apparent.

“Only three of our fields were unaffected by the amount of water,” David explains. “We had to resow fields with spring crops and leave particularly wet headlands and corners bare.

“For the whole industry, it was a moment where we had to seriously look at the resilience of what we do. For us, it meant examining the rotation and finding where we could add greater flexibility.”

A reset

“One of the things that has become clear in recent years, after the Covid-19 pandemic and the wet season last year, is the importance of having something to sell. This isn’t just for the profitability of individual businesses, but for wider food security,” David says.

The arable rotation still comprises winter barley and winter wheat, spring barley, peas and potatoes, but the order is less rigid now.

The only firm rule is that there is at least six years between each crop of potatoes, occasionally stretching as far as seven if circumstances require.

“I never want to force a field. It must be a field in the right condition, for the right crop and in the right year,” he says.

Break crops are integrated in the third and sixth years, if possible, and when suitable David uses minimum tillage, controlled traffic farming and direct drilling to minimise soil movement and the cost of establishment.

However, this year, he admits he has had to use the plough more to provide a reset. This has not been a step away from the sustainable practices used before, but more of an acknowledgement that desperate times have required more traditional methods to keep the business moving.

2025 National Arable and Grassland Awards

Read about all the nominees and buy tickets to the awards night online.

Sustainable farming tools

Indeed, David still avoids insecticides on cereal crops and continues to use tools funded by the Preparing for Sustainable Farming (PSF) programme, including free carbon audits and soil sampling.

“The benefits of farming more sustainably were on clear display last year,” he says. “While nearly the whole farm was affected, you could see how improved soil health made a lot of our ground easier to work. The extra ground on the new farm was a different story.”

Using the soil sampling and carbon audits from PSF, David says he was surprised by the condition of the soil. Nutrient indices were low, showing a lack of previous management, and the soil was very acidic, meaning it needed a good dose of lime.

He says it will take several years to bring the ground up to the same level as the established land.

Some elements of the wider regime are being used, but for the most part David is looking at farmyard manures and livestock to boost the soil’s organic matter.

“I think if you asked any farmer, they would say they know the benefits of using cover crops as a green manure, but after a year like the one we’ve had, it becomes much harder to justify,” he adds.

“It’s not always viable to spend money on seed and operations if there won’t be a financial benefit at the end.”

Bringing it together

Consolidation is key for David over the coming years as he aims to boost soil health across the 100ha that was added and maintain the profitability across the whole farm.

“We were able to get finance for the new ground, now we need to pay for it.”

This hasn’t stopped further investment, as he is set to install a new lagoon and will have to look at machinery maintenance and replacement over the next couple of years. However, the cost of machinery has also led to a rethink.

“Resilience must be in place across the whole business, so I’m keen to keep machinery for longer. Repair what we can, instead of being held to an expensive replacement policy.”

As such, in the two years since we last visited David, the machinery list hasn’t changed significantly. Frontline tractors are still primarily New Holland machines, with the only noticeable expenditure being up-to-date guidance systems for the rest of the fleet to add versatility.

A Claas Lexion 670 with tracks is used at harvest, with straw rotationally chopped and incorporated. Spraying is done with a trailed Amazone UX3200 Super sprayer, unlocked with variable rate and section control, and specified for liquid manure.

Potato establishment kit comes from ScanStone, with harvesting and cleaning machinery provided by Grimme.

A 4m Sky EasyDrill drill handles most of the cereal establishment, equipped with three hoppers for simultaneous fertiliser application and the possibility to spread slug pellets or granular nutrients as required.

For difficult seasons like the one we just saw, a 3m Lemken Solitair drill and two Kverneland ploughs are on hand.

“The cost of equipment means it has to stay on farm for longer. Good-quality second-hand kit is difficult to come by, so we’re looking at keeping what we’re comfortable with, and only investing when there is a clear benefit to the business,” David concludes.